Here will be a quick review of my doctoral research, the highlights, and my thoughts reflecting back on it a few years after the fact. I won’t go into all of the details, I already wrote an entire 200 page dissertation, so there’s no reason to repeat all of that here. Instead, this will be more of a summary and my side comments that are a lot less formal than what would be appropriate for publication in a dissertation. It will also consolidate different posts I’ve made on it so that they are all in one place. So yes, you may have seen some of this before but now you can find it all here!

It is likely that I will edit and add to this as time allows. So check back every now and then to see what’s new.

Dissertation Material:

The first question you have to answer when writing a dissertation is, “Who cares?”. This subject matter made it easy for me to answer that as it all stemmed from a case that was taken to the Supreme Court my first year into my Ph.D. This also gave me an opportunity to do research that was slightly different from my undergrad and masters work in that it was not focused online or on online communities. Though it was different and it focused on Information Science (the focus of my degree), my program was interdisciplinary, so I was able to draw on my anthropological background and ethnographic experience to see it through.

Short Intro:

In 2011, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association 2011 (EMA) (started as Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association 2010) that government entities such as cities and states who wish to use laws and labels they devise in order to restrict the sale of video games to certain age groups were a violation of the First Amendment. SCOTUS stated that there was no need for additional restrictions or ratings since the industry was self-regulated (ESRB Rating System).

“California also cannot show that the Act’s restrictions meet the alleged substantial need of parents who wish to restrict their children’s access to violent videos. The video-game industry’s voluntary ratings system already accomplishes that to a large extent. Moreover, as a means of assisting parents the Act is greatly overinclusive, since not all of the children who are prohibited from purchasing violent video games have parents who disapprove of their doing so.”

P. 2 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n, 131 S. Ct. 2729, 564 U.S., 180 L. Ed. 2d 708 (2011).

Legislating Video Games:

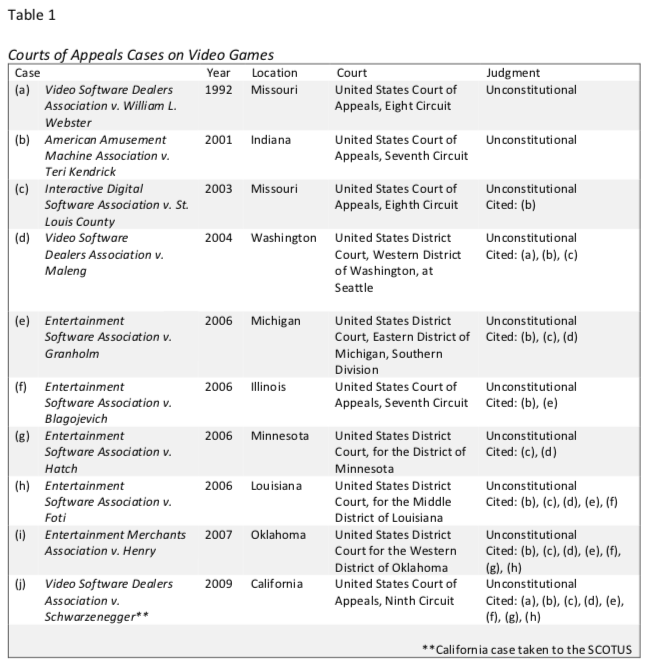

Being a gamer myself, I was intrigued at how this made it all the way to the SCOTUS, so I took it upon myself to delve into the entire sordid history of video game legislation in the United States as a part of my literature review. I created a table that listed all of the court cases that ever appeared at the appeallate level and how they referenced each other. I had such fun doing this that I’ve actually considered going for a JD. (Feel free to use the table below in your research if you find it useful! My citation is below it.)

Harrelson, D. (2016). Rated m for monkey: An ethnographic study of parental information behavior when assessing video game content for their children. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton, Texas.

Regulating Video Games:

Then the ESRB itself became an area of focus for me. Where did it come from? Why did it exist? Funny enough, it all started in 1993 over a feud between Nintendo and Sega and their separately released versions of Mortal Kombat. Turns out that Nintendo’s self-censorship of the finishing moves in the game meant it lost out to Sega’s booming sales of the game in its original version and they were upset over that. (Side note: I played this on an arcade machine at the local burger place during high school every Friday night before football games. No one cared that a kid was doing this in the early 90s.)

“The official account of events that lead up to the hearings is that U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman (Democrat of Connecticut) became concerned about video game violence when Bill Andersen, his chief of staff, told him about a hot new game named Mortal Kombat. Andersen’s nine-year-old son wanted a copy of the game, but Andersen, having heard that it was “incredible violent,” did not want to purchase it for him. Out of curiosity, Lieberman suggested that they get a copy and see what it was about.”

P.467

Kent, S. L. (2001). The ultimate history of video games: From pong to Pokemon–the story

behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world, Rocklin, CA.: Prima

Communications, Inc.

Parents and Video Games:

In reading about the ESRB, there was this little nugget that I thought was particularly relevant:

Not only did the decision to remove the violence hurt sales, it also offended many Super NES owners. According to Howard Lincoln, Nintendo received thousands of angry letters, including a few letters from parents, warning Nintendo not to censor their children’s games.

P.466

Kent, S. L. (2001). The ultimate history of video games: From pong to Pokemon–the story

behind the craze that touched our lives and changed the world, Rocklin, CA.: Prima

Communications, Inc.

This of course made me want to learn more about parents use of the rating system. Do parents actually use the ESRB? If so, how? If not, what do they do instead? And I wanted to understand whether or not parents felt legislation was the answer to video game regulations. This brought me to two major Research Questions:

Research Question 1

When considering the appropriateness of video game content for their children:

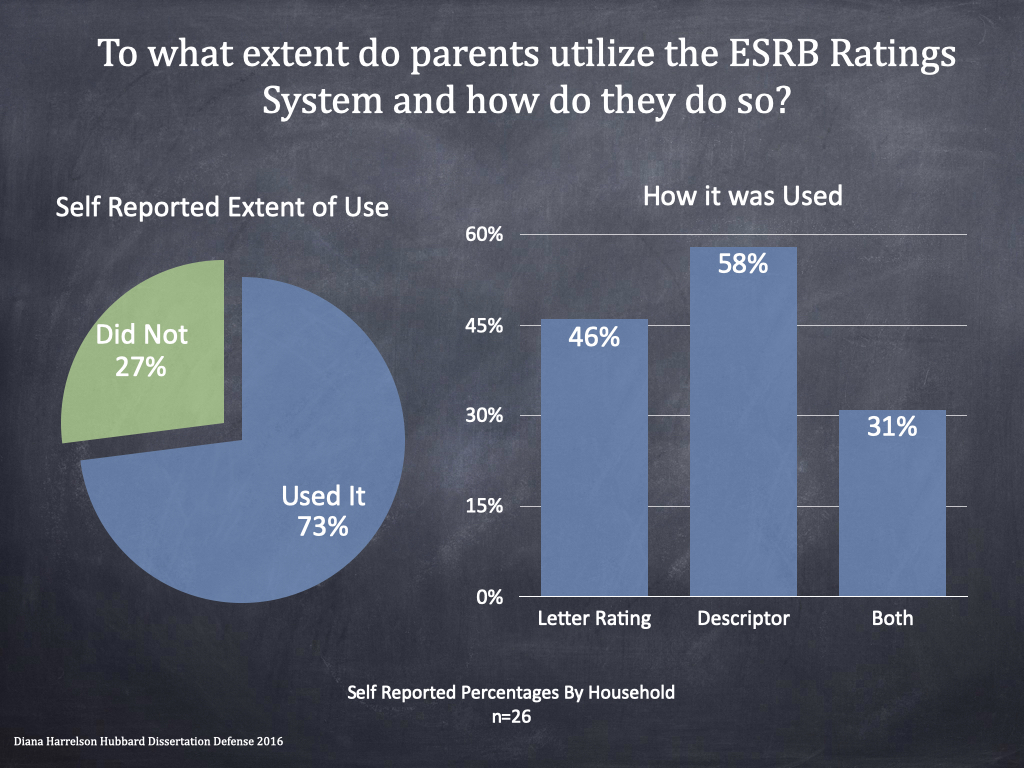

To what extent do parents utilize the ESRB Ratings System and how do the do so?

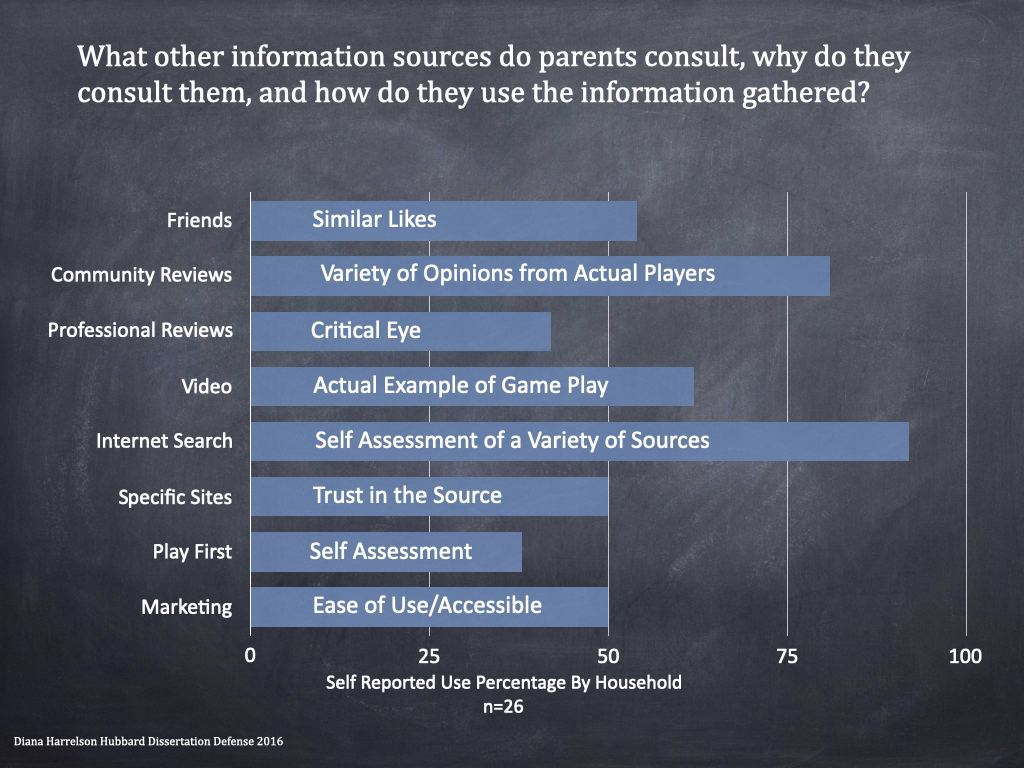

What other information sources do parents consult, why do they consult them, and how do they use the information gathered?

Research Question 2

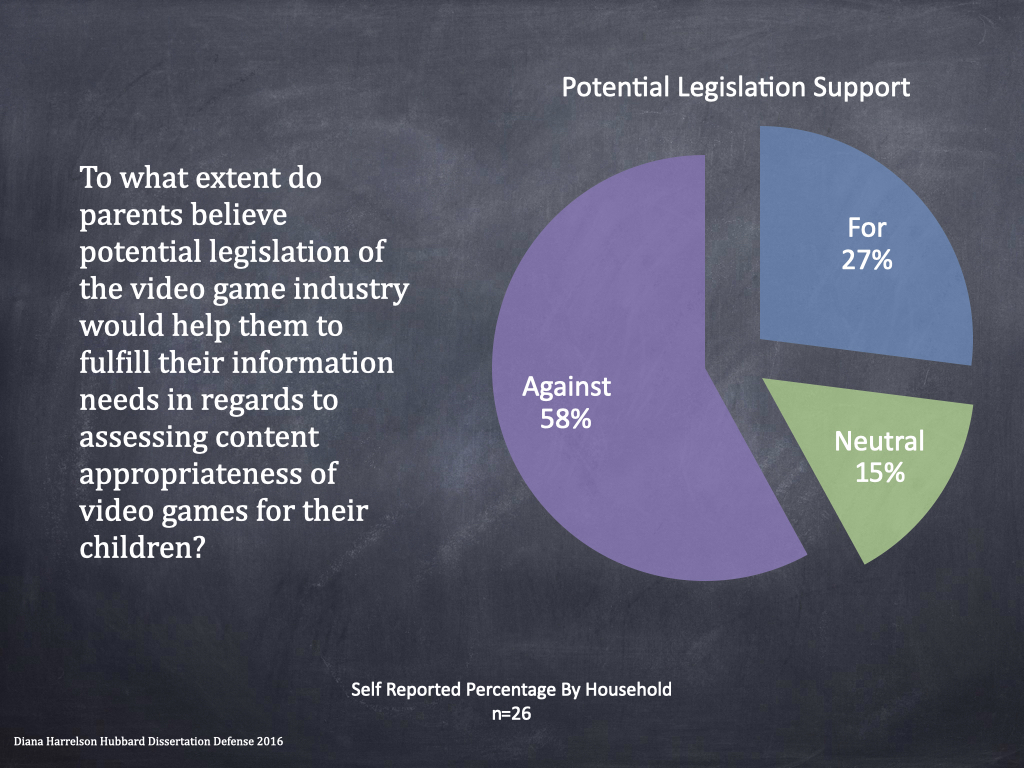

To what extent do parents believe potential legislation of the video game industry would help them to fulfill their information needs in regards to assessing content appropriateness of video games for their children?

So, I went and talked to a bunch of parents (and some of their children) in their homes (which played a major part in the research) about what they thought of video game ratings and legislation. Following are some of the high level details from the study.

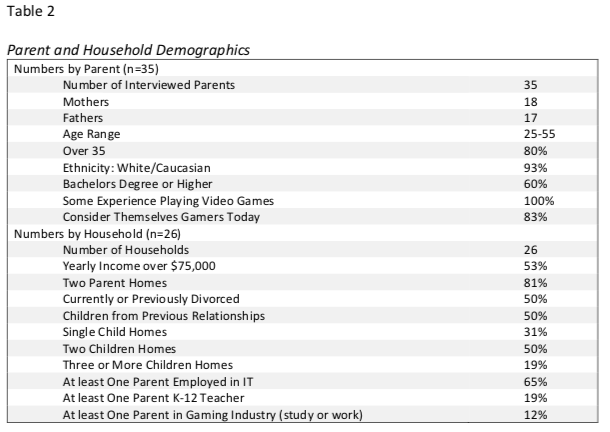

First, we should review who I talked to.

Breakdown of Parent Demographics:

Harrelson, D. (2016). Rated m for monkey: An ethnographic study of parental information behavior when assessing video game content for their children. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton, Texas.

Child Demographics:

The study included 39 qualifying children who met the age requirements of 4 to 17, out of a total of 50 belonging to the parents who participated. Parents provided data on all 39 qualifying children, and 11 of them were able to represent themselves in the study. Over half of the 39 children were male (59%). The average age of all 39 children was 11, with almost half (46%) falling between 4 and 9 years old; a little less than a quarter (23%) were between 10 and 12 years old; and almost a third (31%) were between 13 and 16. The average age they started gaming was 3.5. The majority of the 39 children (88%) attended public school, and most (88%) participated in some sort of extracurricular activities including band, swimming, baseball, scouting, and more. (P. 64 – Harrelson, D. (2016). Rated m for monkey: An ethnographic study of parental information behavior when assessing video game content for their children. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton, Texas.)

Now let’s go over the highlight reel.

Key Findings

- There were no parents in the study who were able to definitively name all of the parts of the ESRB Ratings System or all six ratings and over two-thirds did not know what process games went through to get rated. This resulted in the majority of interviewed parents knowing little to nothing about the ratings system even if they claimed they used it.

- Interviewed parents had very specific criteria they used to judge video game appropriateness against and once any of those lines were crossed, the game was considered unsuitable. Though violence was a concern for interviewed parents, perceptions of violence were far more nuanced than the ESRB Rating System descriptors were able to convey, thus many had to do further research to properly assess the game and make sense of the content. Sexual content, however, was of a far higher concern than violence even for those interviewed parents who considered themselves very liberal in the types of games they allowed their children to play.

- Interviewed parents with special needs children considered the needs of their child and the ability for a game to help him or her as more important than staying within content that was age appropriate.

- Based on the interviews, every family’s and child’s needs are different, including children within the same family. Therefore, a single information system, such as the ESRB Ratings System, may never be able to completely fulfill all of a parent’s information needs as they attempt to bridge their knowledge gap. As long as it provides a place to start, that may be all it needs to do.

- Relevant to the previous finding, interviewed parents attempted to bridge their knowledge gaps in multiple ways in order to assess game content and make sense of it. These included using the ESRB Ratings System, Internet searches (including specific sites as well as more general results) to find game reviews (both community and professional), game marketing (including websites, packaging, and commercials), and Let’s Plays (video game play-throughs).

Credibility of the gaming information source was very important to interviewed parents. They cited both the source of the documentation as well as the reputation of the reporting source to be important factors in establishing credibility. - Though a few interviewed parents were in favor of a law, most were not. Those in favor cited it as an extra level of protection or as something they thought was already in place. Those not in favor cited issues with enforcement, the inability for laws to really assist them, as well as a general dislike of having the government interfere with their role as parents.

High Level Research Results

Video Games

Over 200 games were mentioned throughout the course of the interviews, not including the various versions of multiple game franchises. The top three most mentioned games were Minecraft (85% of households), followed by Grand Theft Auto (65%), and then World of Warcraft (42%). Almost two-thirds (64%) of the 39 children played M-rated games and over three-quarters (77%) played T-rated games. None of the children in the study were old enough to purchase M-rated games and only 31% of the 39 children were old enough to purchase T-rated games.

Video Game Devices

Participants played console, computer, and mobile/tablet games equally (88%). Handheld games (58%), followed by web-based (38%), and then educational (35%) rounded out the list. Over three quarters of all 26 households (77%) used some sort of cloud gaming services such as Steam, Origin, Xbox Live, or PlayStation Network. All households downloaded games digitally, whereas only about three-quarters (77%) still bought physical game media.

Video Game Spaces

The majority of game spaces (58%) were publicly shared spaces with the family. Very few (8% of all households) had completely private spaces where stationary devices such as computer towers or consoles were located in children’s rooms. The remaining households (35%) had mixed game spaces due to the use of portable electronics such as laptops, handhelds, and mobile/tablet devices. The majority of households (69%) had some sort of time restrictions placed on video game play; however, less than half of them (39%) considered them to be strict rules.

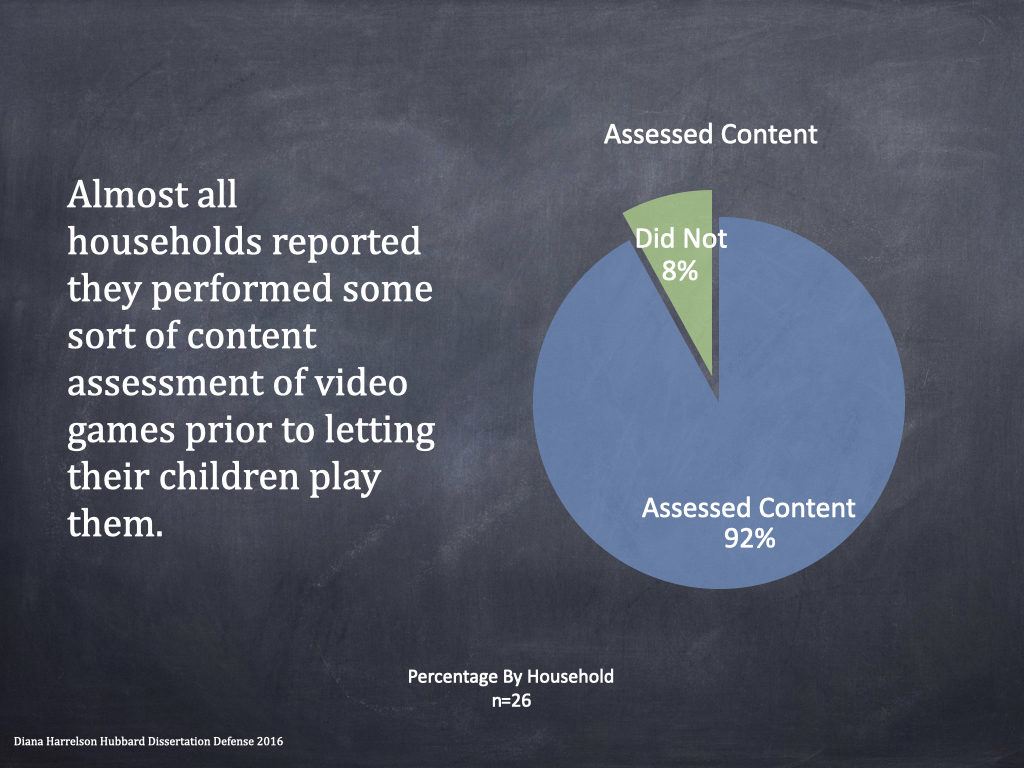

Parental Assessment

An overwhelming majority of the 26 households (92%) performed some sort of assessment on video games before their children were allowed to play them. Almost all of the 26 households (92%) discussed video game content with their children, and most (85%) stated they knew their children to self-regulate and/or they trusted their children to only play the games of which they knew their parents approved.

Parental Involvement

Almost three-quarters of the 26 households (73%) watched their children play video games and many (69%) played video games with their children. Over half (54%) of the 26 households allowed their children access to the Internet to either play online video games such as massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPG i.e., World of Warcraft) which can only be played online, or to play standard multiplayer video games with others online.

As to the specific research questions previously mentioned:

Answering the Research Questions

Considering Use of the ESRB:

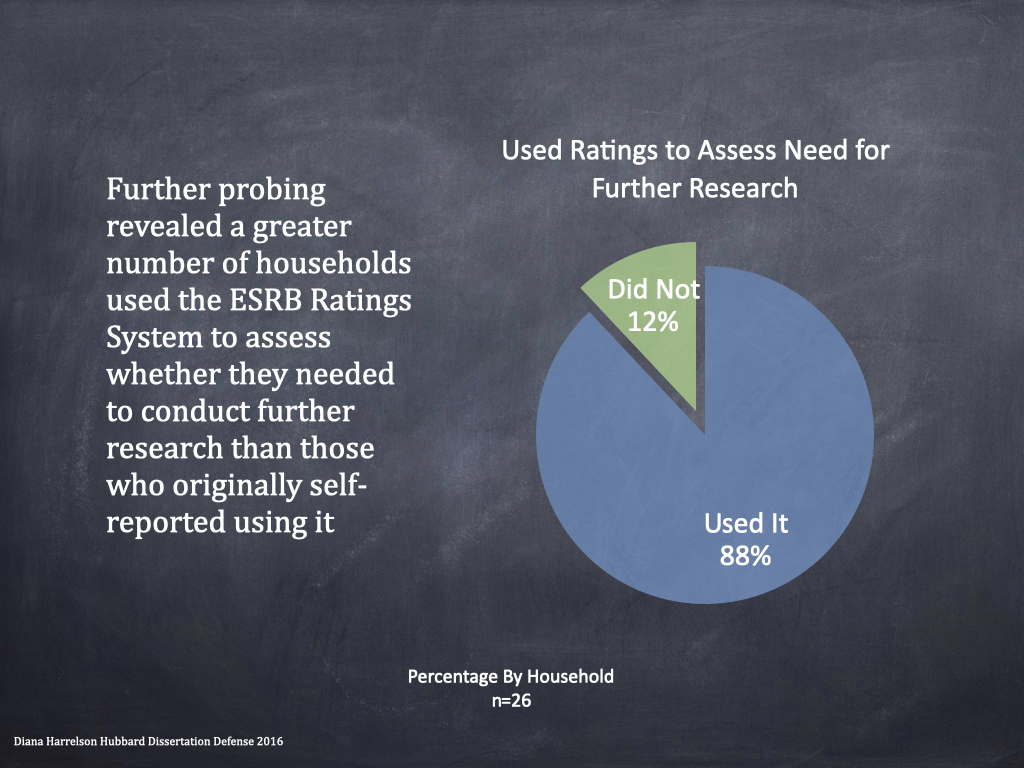

Though 27% said they did not use the ESRB, when probed further, it was found that almost half of them used it as a way to determine if further research was needed.

And parents used a lot of different sources for further research.

Considering Legislation:

To break this down further – 42% of Households were For or Neutral toward Potential Legislation (n=26) vs. 31% of Individual Parents For or Neutral toward it (n=35). This further breakdown was warranted because where there were multiple parents interviewed from a single household it was often found they had a difference of opinion on legislation.

The Big AH HA!

One of the things my committee wanted from me was what was the ah ha moment from the research? What would make this research unique, worthwhile, important for future research? This made me take a step back and really assess the entire thing holistically. When I started looking at the numbers across the children’s different age ranges and how parents reactions and interactions changed drastically with different age groups I saw a pattern emerge.

Granted, patterns in qualitative research, while important and can lead to some significant findings, should always be tested further to validate them. My study did not do that. Instead it set the ground work of a model to be tested and to evolve as needed. The following will be a discussion of that model.

Before I delve into the model, I’d like to get a few important academic things out of the way first. To begin, my Ph.D. is in Interdisciplinary Information Science. I used a social informatics (SI) epistemological framework. You can skip the “from my dissertation section” if you’re not interested in the academic background of how this model came about.

From my dissertation:

In general, SI research examines the design, uses, and implications of information and communications technologies (ICTs) in ways that account for their interactions within institutional and cultural contexts (Kling, Rosenbaum, & Hert, 1998, p. 1047). SI bridges technology and society with a focus on ICTs from users’ perspectives. It is a field that many disciplines have contributed to, including anthropology and information science. In essence, it is an interdisciplinary field that can “serve as a conceptual home for those who are interested in contributing to studies of ICTs and social and organizational change” (p. 1048).

Dervin and Nilan’s (1986) sense-making model, which focuses on users and how they overcome, or bridge, information gaps, provided the methodology for this SI approach. Dervin described the model as consisting “of a set of conceptual and theoretical premises and a set of related methodologies for assessing how people make sense of their worlds and how they use information and other resources in the process” (Dervin & Nilan, 1986, p. 20). Others have described it as an approach “characterized by its focus on constructive, active users, subjective information, situationally, holistic views of experience, internal cognition, systematic individuality, and qualitative research” (Pettigrew, Fidel, & Bruce, 2001, p. 43).

With the focus of Dervin’s model on qualitative procedures such as interviews and neutral questioning (Dervin & Nilan, 1986, p. 20), grounded theory as an analogous methodological approach was chosen for this study. Strauss and Corbin (1994) defined grounded theory as “a general methodology for developing theory that is grounded in data systematically gathered and analyzed” (Strauss & Corbin, 1994, p. 273). It is unique from other methodologies in that it “evolves during the actual research, and it does this through continuous interplay between analysis and data collection” (p. 273). To that end, the model developed for this study evolved with simultaneously conducted research and analysis.

(p.12-15 Harrelson, D. (2016). Rated m for monkey: An ethnographic study of parental information behavior when assessing video game content for their children. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton, Texas.)

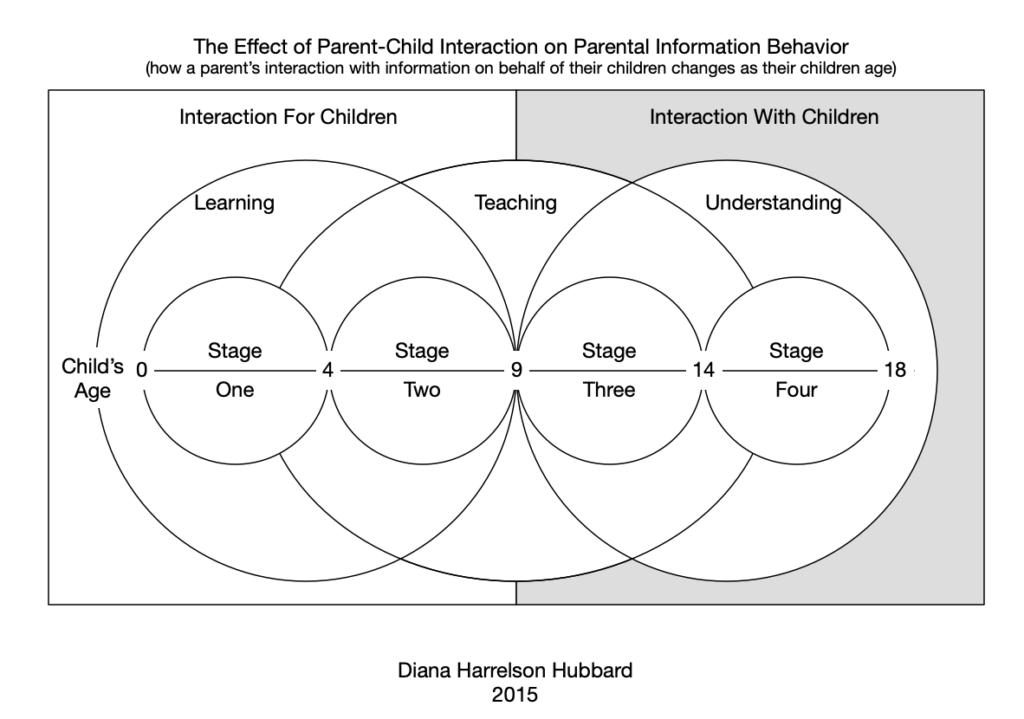

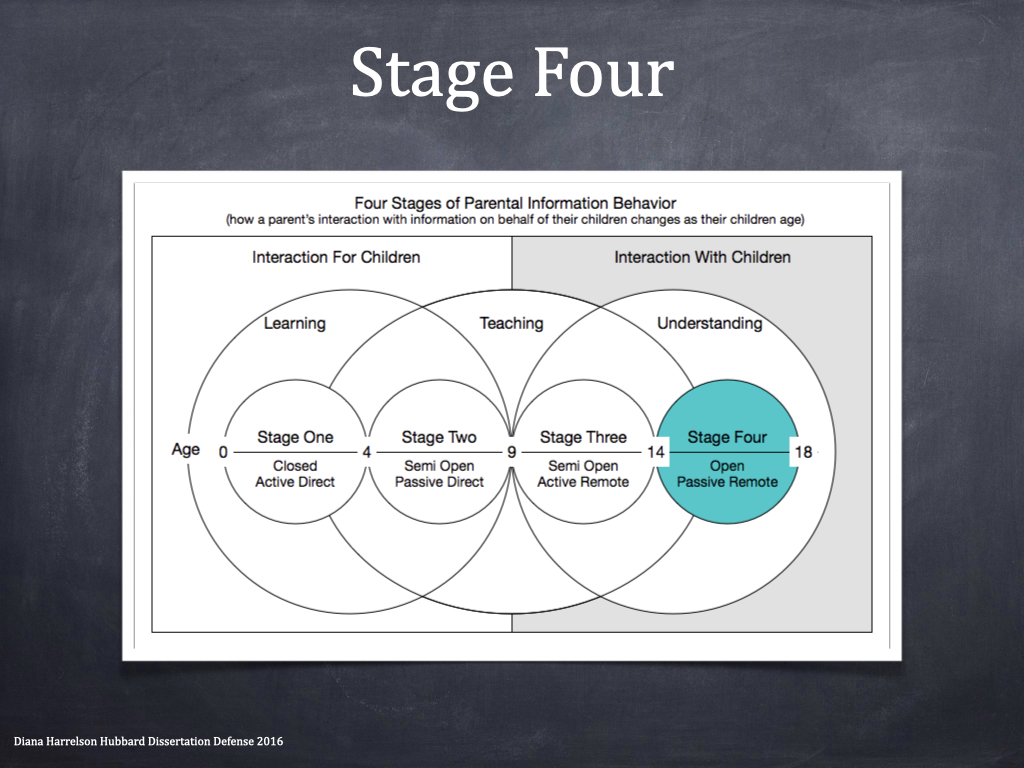

Model: The Effect of Parent-Child Interaction on Parental Information Behavior

This is simplified from my original version (see below), but I think that makes it easier to utilize for other studies and other types of information behavior.

Breakdown:

The model consists of 4 different parts.

- The first is the dividing line that separates Interaction For Children and Interaction With Children.

- The second are the intersecting domains of Learning, Teaching, and Understanding

- The third is the age timeline from 0 to 18

- The last are the stages from 1 to 4

Part 1:

Concept – the interactions of parental information behavior and their children changes as their children age.

Moving from interacting FOR children to interacting WITH children. This defining line made itself evident after evaluating how parents of different age groups interacted with information when it concerned their children and how *successful that interaction was depending on the type of interaction and the child’s age.

It became evident after evaluating the data that parents who had more conversations with their older children and who made decisions with them had more success in having open and clear communication about media and its appropriateness than those who decided everything for their children and subjected them to a more authoritarian rule. Those parents who worked with their older children were less worried about their children’s interactions with media than those who preferred to do things for them.

*success is of course subjective here but usually included the lack of a need for discipline or worry because the parent/child relationship was such that there was a clear level of trust or at least an evolving one that they were working on together

Part 2:

Concept – the parental information behavior domains parents interact in as it concerns their children change as their children age.

The learning domain consists of all of those things parents do to learn what they need in order to parent. This includes the information rush parents go through when they find out they’re expecting as well as interacting with it to fulfill their children’s information needs before their children are able to do so on their own.

The teaching domain consists of the information behavior as it relates to the parent helping to teach the child whether it be a homeschool situation or supplemental to an external student learning system. It is also about teaching the child how to interact with information on their own. This environment bridges the For children and the With children as the child ages and becomes more independent in their own information behavior.

The understanding domain is the beginning of a mutual understanding between the child and the parent as the child becomes independent in their information behavior and the parent seeks to understand their child’s new information needs and behaviors.

Part 3:

Concept – tracking parental information behavior as the child ages from 0 to 18.

Though my research focused on recruiting parents of children 4 to 17, parents discussed younger and older children as well as children’s behaviors when they were younger. For example, the average age most children in the study started gaming was 3.5. This timeline is most important as it relates to part 4.

Part 4:

Concept – parental information behavior, as it concerns their children, tends to go through 4 stages corresponding to the child’s age. **

- Stage 1 – Birth to Age 4

- Stage 2 – Age 4 to Age 9

- Stage 3 – Age 9 to Age 14

- Stage 4 – Age 14 to Age 18

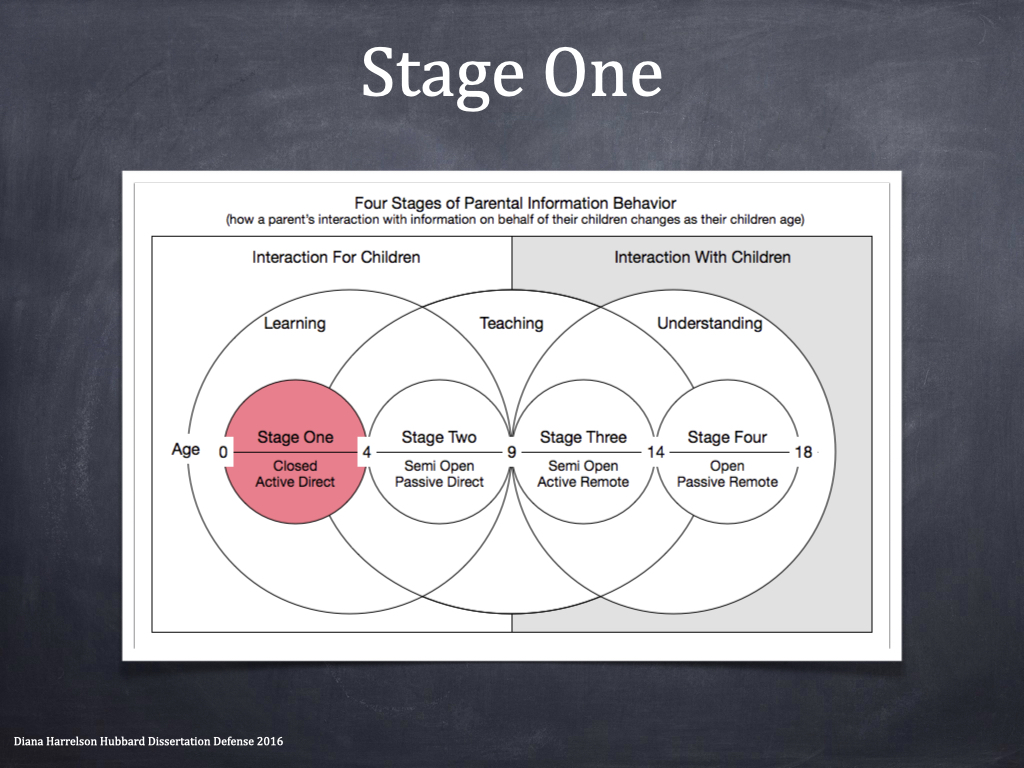

Stage 1

Birth to Age 4

In this stage the parent’s information behavior as it concerns their children is for their child and focuses primarily on learning about parenting and then transitioning into teaching as the child hits pre-school age.

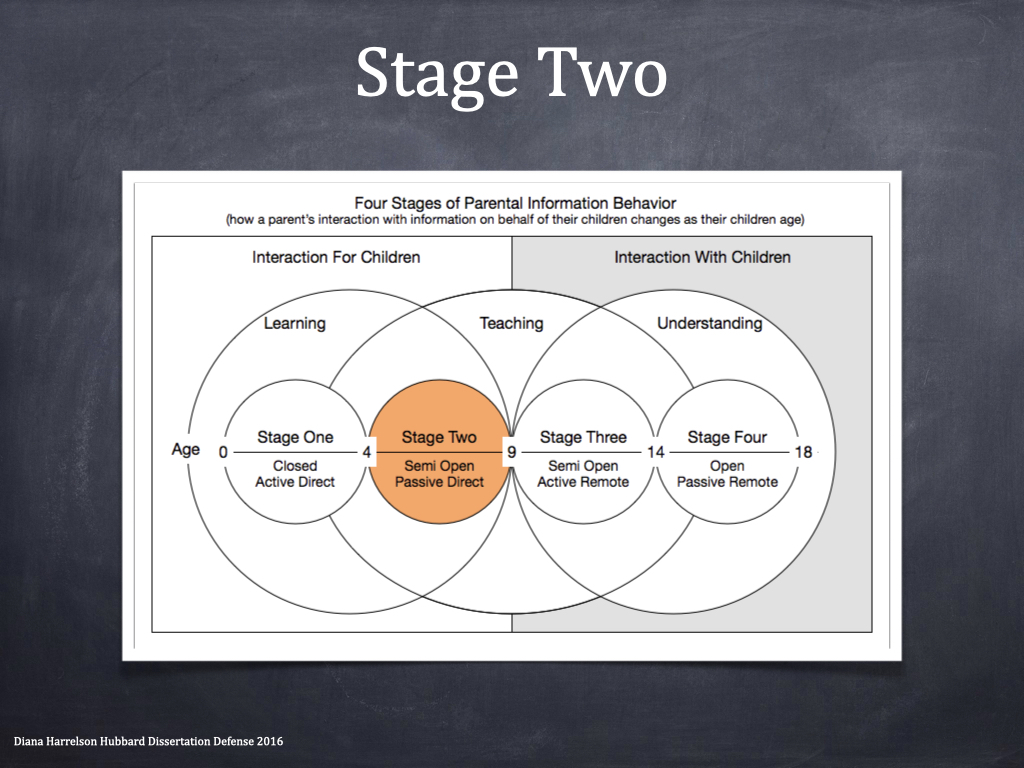

Stage 2

Age 4 to Age 9

Parental information behavior in this stage is a two pronged approach still on learning, but with an emphasis on teaching. Here, the child starts to become more independent and starts to be able to take on their own information needs, but they tend to still have a lot of needs that only their parent can fulfill. Additionally, due to their young age, they still have a lot of supervision.

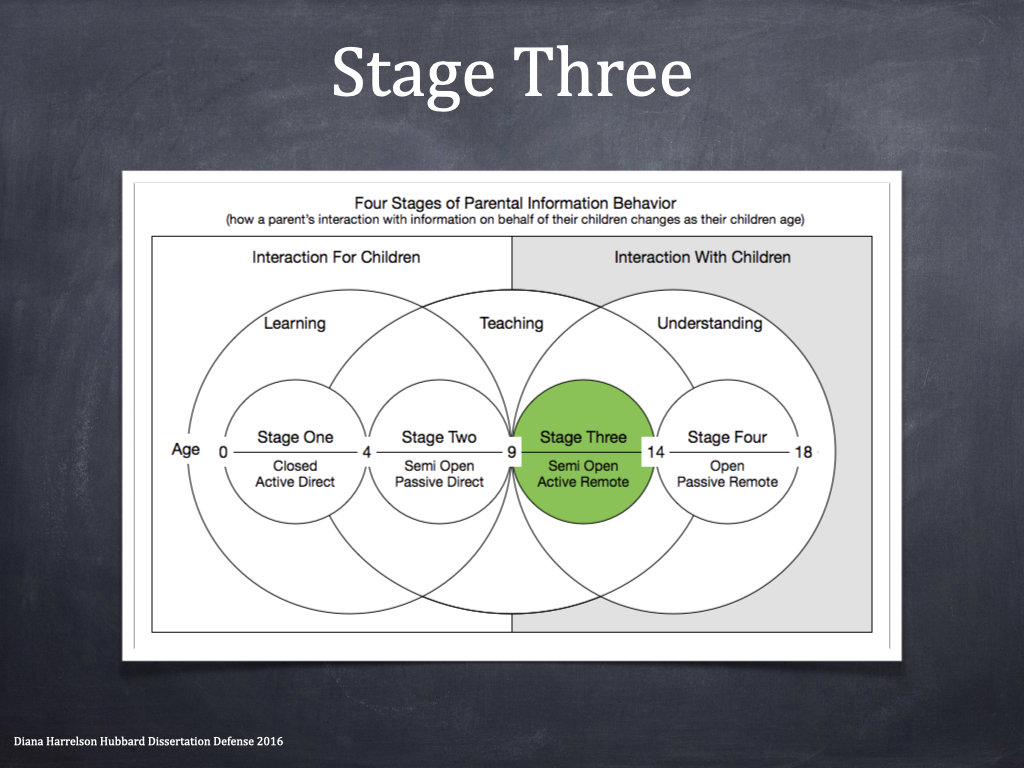

Stage 3

Age 9 to Age 14

This is the stage where parents were most concerned in my study. This was for two important reasons. One, children were becoming completely independent in their own information behaviors needing less assistance from their parents. And two, this is the stage where most children start to enter puberty. Here, parents were less concerned with violence and more concerned with sexual content or other improper things like language and drug use.

Stage 4

Age 14 to 18

By the time the child enters high school, or just after, and until they are deemed an adult by culture and society there is an interesting phase where the child can in some cases surpass the parents abilities and understandings when it comes to media and information behavior as it pertains to popular culture and even technical aspects. If a parent has not fully transitioned from For to With and has not moved into wanting to understand what their teen is doing and why, from the teen’s perspective, they will likely lose all control, access to, and input on the teen’s media consumption. This is especially the case the more authoritarian they become and this will cause the teen to hide their information behavior instead of share it (or at least a portion of it) with their parents.

**Side note: There may be differences as to how parents approach these stages with subsequent children and that may also depend on the age gap between their children. Additionally, I did NOT do any research on child information behavior specifically, nor did I focus on any previous research on children and media. My research was focused solely on parents, so this can certainly be added to over time as needed to focus on the needs of children if it makes sense to do so.

Now, if you review my presentation of my dissertation defense (the presentation most of the graphics in this come from rather than the dissertation itself), you will see a more detailed version of this model, which I will add below.

Added details: Any information behavior activities the child has at this stage are actively and directly observed by parent and tend to be on a closed system (no outside access).

Added detail: At this stage, parents tend to provide their children their own devices, but in a locked down mode, which allows for semi open interactions that can be supervised as needed (passive) but in the presence of their parents (direct). Online access usually comes in the form of white listed programs or school related needs.

Added Detail: During this stage children become more independent in their media use and information needs as they need less help from their parents in order to do so. While the system may still be only semi open (some lock downs still exist), the child is now able to interact with their media outside of the parents purview. This new independence tends to come with a cost though as the parent becomes more active in paying attention to what their child is doing via remote observation (nanny programs).

Added Detail: In this stage parents had the least amount of influence or control over the information with which their children interacted, thus their children made most of their information behavior decisions on their own. While parents still made decisions at this stage, children tended to have more influence on the decisions being made. Here there were natural barriers to Mature content which included initial cost and access to a credit card.

Though most teens had open access to interact with information as they pleased in that they were less restricted the older they were, their parents still had control over the access itself and would remove wireless/mobile access when needed (passive monitoring – decisions made here were usually based on grades, attitude etc.) instead of trying to control access to specific things at an application level. This meant it ended up as an all or nothing for the teen. As teens tend to be very protective of their online access, it was a line few wanted to cross.

So? What’s the point?

From my dissertation:

This model was designed to show how interconnected parent-child interactions are with parental information behavior and the effects of this interconnectedness on it. To put it simply, parental information behavior cannot exist without this interconnectedness and it is because of this interconnectedness that it needs to exist as well as persist and change over time.

The examples [see dissertation starting on p. 169] were provided to show how parent-child interactions affect parental behavior on a multitude of levels including information, communication, and decision-making strategies. Additionally, they were to show how this behavior both changes and becomes more complex as children age. Thus, a ratings system that provides the same type of information for every level at every stage may lose the ability to successfully help the parent as their child ages and they reach the later stages, which is arguably when both parents and children need it most.

The major take-away is that children can greatly affect how and why their parents interact with information and it goes well beyond age in the sense of restricting material based on age alone, especially the age ratings that are in place today. Finding ways to educate and assist both parent and child, to provide information in such a way that both can interact with it, and each other, is key to successful family information behavior and any information system that wants to support it.